‘Bun this.’ The immortal words that led to me converting to Team iPhone in 2020. The ‘calm’ explanation behind my treachery was that I was getting marketing-related gigs, and anyone who does marketing does it on an Apple device. (Seriously, you try and get a marketer on Windows and you’ll feel the withering side eye). But the true story behind my transfer was that I dropped my Samsung on Leamington Parade and it died on a day where I had Evri deliveries and back to back meetings. Taking it as an omen, the cartoonish rage I had on the pavement led to a howling disavowal of all Androids henceforth, and the beautiful phone I have now – an iPhone 13 Pro. This glorious workhorse of a phone has been the perfect tool for this phase of my life. It marked a change from my years of flitting between LG, Motorola, Samsung, and Sony Ericsson – which as I list them out – sounds hideously wasteful as I’ve had my current phone for four years. Why am I being this detailed? It’s so when I read back on this piece, I want to hold this make and model with as much bemusement and warmth as I do with the other phones I’ve put in storage- each emblematic for certain phases of my life.

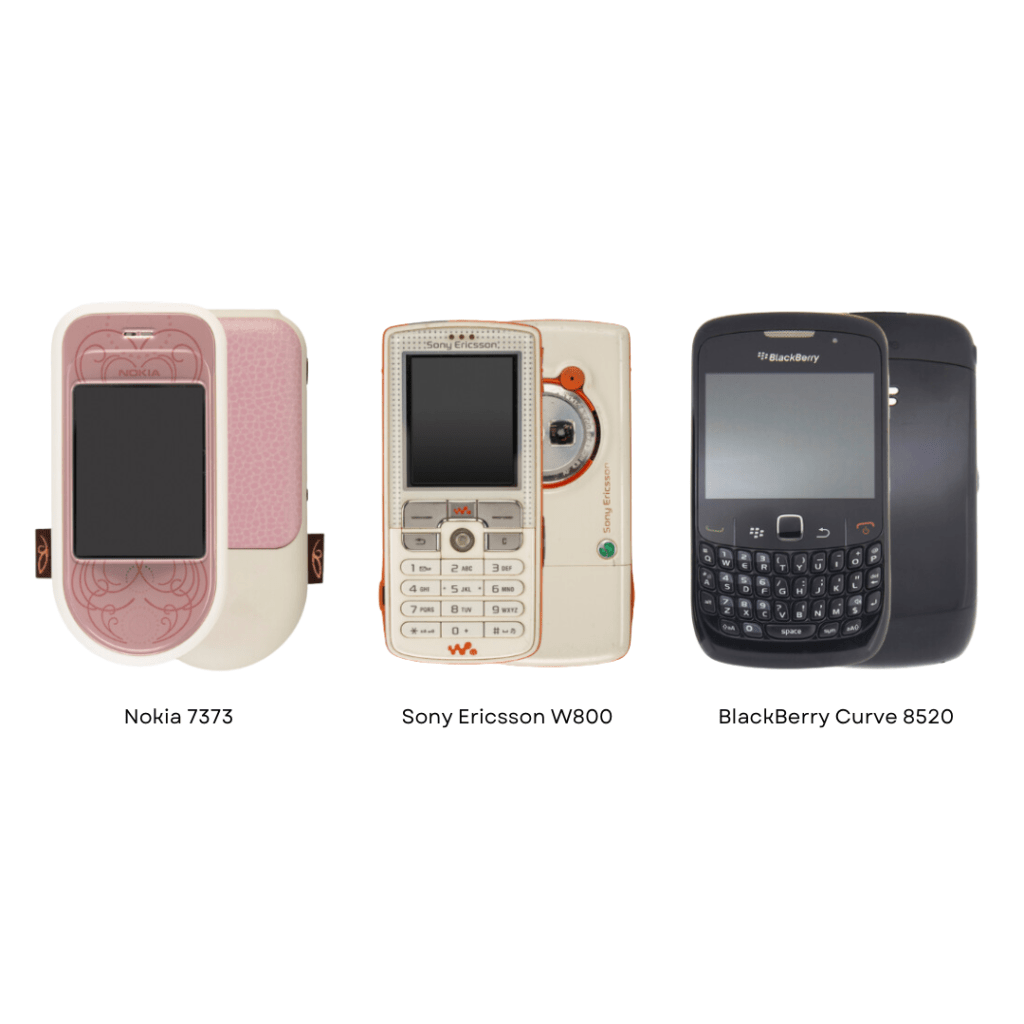

Ironically, it was with said iPhone 13 Pro that I messaged another about how much we missed the BlackBerry Curve 8520. That was the phone I got after saving my EMA money. I’d at last joined the wave of yapping Bad Bs and the cool 2010 teenagers who needed to have the same encrypted messaging service that kept BlackBerry alive for US state officials. While BlackBerry has opted out of the smartphone market (🕊️), it continues to have a powerful hold over millennials – including me. I did what any chronically online person does which was to create a very scientific poll on my Instagram to ask others about their youth phone of choice. Each DM I received made clear that when we delved deeper, there were other phones that held a dearer place in our hearts too.

The aesthetic

As phones became powerful and embedded in everyday use, they’ve come to operate as part diary, part pop culture symbol, and part snapshot into your school’s lore. For millennials who navigated the heady days of MSN, MySpace, the rise of Facebook and Twitter, phones facilitated and represented the blurred boundaries between social cliques. ‘In the ‘connected’ age of the Internet, the global ‘reach’ of local youth scenes has been both extended and accelerated,’ states Bill Osgerby, writing for the Museum of Youth Culture. ‘And developments like the spread of social media may also have increased…the rigidly defined scenes of the past giving way to a universe of hybrid “style-fusions.”’

Jaz Morrison, a multidisciplinary writer and artist-curator from Birmingham, recalls these years as the era of ‘when the phone itself was the aesthetic.’ It’s why we associate Paris Hilton with the pink Motorola and Kelly Rowland with the Nokia 9210 Communicator in Dilemma. Before Apple’s sleek iOS dominance, phone brands were distinguishable from one another until Android became their operating system of choice. (It’s why for example, a Nokia and a Motorola felt different to a Samsung). If not the software, hardware changes can be tracked in the Mobile Phone Museum‘s catalogue with collections such as: ‘Phones in Movies’, ‘Best Selling’, and my favourite: the ‘Ugliest.’

It was the 2007 release of the first iPhone which pushed innovation forward, including the birth of the LG Cookie. For Jaz, ‘Before the iPhone craze I remember having an assortment of bizarre phones, from a Nokia brick with a Union Jack shell, to the Samsung Genio Touch that my parents had bought me instead of the coveted LG Cookie.’ Despite LG’s exit from the smartphone business in 2021, the LG Cookie casts a long shadow to this day. Introduced in 2008, the LG Cookie KP500 made the touch screen affordable. There were various iterations and accessories (including one version which had a solar powered charger which was innovative for its time).

‘I would sit and look up LG Cookie phones during Year Nine ICT classes, History classes, English class- literally any chance I could access a computer,’ Sky Dair, a writer and multi-disciplinary artist in London tells me. ‘The stylus built into the top felt like the ultimate way to express my sense of prep as a 14 year old in an inner city London school and so I coveted this phone deeply. The pink case I now realise spoke to my inner Sofia Coppola girly and it felt like if I had this phone, I could ascend to the next level of Disney Channel TV star that I longed to be.’

We showcased our vibes through the choice of phone shapes and mechanisms, and personalised our devices with ‘jewellery’, decorative cases, stickers on buttons, and ringtones. When Sky finally got their LG Cookie, ‘the phone grew with me, as I headed into emo and insisted everything would now have to be black and very serious and usually covered in skulls.’

On another patch in London, I didn’t totally bedazzle, I copied my cousins and attached bindis to my first few phones. It was a nod to how tablas were in every Timbaland hit and Bend it Like Beckham made being South Asian cool. But my attempt at design was pretty mid compared to Sky who ‘used gloopy old nail polish to cover the entire case of the phone in a very serious act of DIY… I painted the name of my favourite band at the time “The King Blues” on the back with a black background and blue wobbly text. I had to prove that I was very dedicated to the cause of anarchist ska punk spoken word rock and my LG Cookie really took the brunt of these teenage years. Holding my current phone in my hand, I can still feel that phone with all the layers of bumpy nail polish.’

All this goes to say that youth culture is never static or homogenous.

‘As I get older,’ begins Jaz. ‘I find myself longing for the “Gaudy Days.” Back when everything was bright and colourful and asymmetrical and novelty. Back when creations actually felt like extensions of its creator, and not just a product to flog.’

The sounds

For millennials now in their thirties, the years of our newfound Auntyhood run alongside the years of how smartphone designs have standardised. I felt this keenly when I taught a confused young ‘un how to text on a Nokia in 2017. I spoke of the obsolete skill of being able to silently text without looking, and with buttons so small that you had to hit a CerTaIn Way otherwise you’d lock ‘em. He had that ‘sure Jan’ face as my words couldn’t capture the rapturous satisfaction of answering a call with a slide, ending one with a flip, or the soothing clickety-clack, tippity-tap QWERTY keyboard.

While Jaz didn’t procure the LG Cookie, the Nokia 7373 holds a special place in her heart. Introduced in 2006, it was part of the sensually named ‘L’Amour Collection’ and an upgrade of the Nokia 7370. Its ornate partterned, swivel design hid the keypad and was a move away from how Nokia continues to be renowned for being shaped and reliable like a ‘brick.’

‘It was so retrofuturist (to me!!!) that I happily ignored its powdered pink colour,’ remembers Jaz. ‘If the packaging included earphones, I lost them early on, so I would blast the 99p TrueTones™️ ringtones out loud as I walked home from school. My favourite tone was Rihanna’s Umbrella. When I tried – and failed – to capitalise on Orange Wednesdays, it was with the Nokia 7373 that I first attempted it.’

Jaz touches on the routines that run alongside phones. I’d forgotten how Umbrella was my worst alarm because the thunderous cymbals and Jay Z’s ‘uh huh uh uh’ annoyed my family each morning. I’d also forgotten how Orange Wednesdays were a staple in bringing young people together and anecdotally encouraged many a pre-teen romance. (You’d receive 2 for 1 cinema tickets on a Wednesday, a 2003 offer that was discontinued in 2015 when Orange became defunct after EE bought it).

Whereas for Tarrine Khanom, a photographer and visual artist from London, they experienced this era of phones differently as an older Gen Z. They played the games that were built into their dad’s Nokias and had fond memories of their, ‘older brother having a Sony Walkman and I loved the white and orange of it.’

When it came to music, from the Instagram poll, the majority held the Sony Walkman phone to high prestige. The Sony Ericsson W800 was the first of its series. Launched in 2005, its relative affordability appealed to those who didn’t have an iPod or want to carry an MP3 player. It was an astute move that touched on the Sony Walkman heritage as chances were that it was a 70s/80s music-lover parent who’d gift this phone to their millennial child. And boy would the Walkman phone-holder let everyone know that they had the best sound system and Bluetoothed/Limewire library in the postcode. From the DMs, it’s the phone affiliated with glee – it belonged to the bard who narrated Keisha the Sket during break and the jester who’d make prank calls at lunch. This was the phone for the loud personalities, but does an equivalent exist now?

I can’t help but think of Jaz’s words that ‘Smartphone conformity might just mean that we’ve reached the end of an era.’

What’s next?

A cursory scroll on Carphone Warehouse’s website might leave you with the assumption that we’re reaching the end of mobile phone innovation. Phones with keypad buttons are still around but dubbed as ‘senior phones’ on Amazon. While there are funky phone cases available, the Mobile Phone Museum’s catalogue will show you how phones have toned down over time. It reminds me of what Riccardo Falcinelli’s wrote in Chromorama: ‘Colour is baroque and immoderate; monochrome is measured and tastefully correct.’ Short of smartphones gently reinterpreting the humble rectangle, the extreme innovation of note is a touch-screen flip smartphone, and some that are gargantuan enough to become tablets. Given their price points, it’s not as popular, so smartphones don’t seem as dramatic to us regular Joes.

Certain functions have been lost or improved as developments in phone technology dismantled the concept that you had to go to a public, physical place to access the internet. Millennials had – what felt inconvenient at the time – the choice of the family PC, the PCs in their school’s IT room, the internet café, or the one in their local library. We can see traces of life before smartphones in our language, surroundings, and the way we consume culture. To name a few:

- Charity shop inventories reflect how we don’t collect physical copies of songs, movies, games and software any more as it’s all on the cloud.

- On a good day, you might catch older generations referring to Apple/Google Maps as the ‘sat nav.’

- Piracy and broadcast television isn’t what it was as Netflix and Spotify are staples to our consumption of shows and movies.

- Snapchat and Instagram have changed how we instinctively take photos in portrait instead of landscape.

- Gone are the days of texting music channels, physically going to the bank (as much anyway), and the mustached uncle on the high street who’d fix your multi button phone with surgical precision.

If rituals and industries haven’t been lost, they’ve adapted as phones, like any other gadget, reflect the society we’re in. We’re in the age of hyper connectivity which makes it hard to use ‘less smart’ phones with our techy jobs, two-factor authentication on everything, and our ‘just in case’ compulsive need to record everything. Tarrine remarks, ‘Phones used to actually fit in the palm of your hand and only had a couple of functions. Now we can literally do anything with our devices. I was too young to experience or know of it but I do wonder how it used to be before when we could leave our devices at home, when it was separate from us and not integral and essential to our lives [socially, careers etc].’

Tarrine isn’t alone in pondering this. Last week’s C4’s documentary series Swiped: The School That Banned Smartphones followed a group of year eight pupils have a smartphone-free three weeks. It explored how young people and parents, schools, and politicians navigate the consequences of intense smartphone use. As Dr Rangan Chaterjee puts it, smartphones are ‘changing the fundamental nature of what it means to be a child’ with 90% of eleven year olds owning one. Cutting back improved their health and relationships but I was more interested in how the parents of the children who’d gone on the digital detox were finding it. They’re my agemates navigating new terrain.

It is perhaps why as Tarrine states ‘Nostalgia, Y2K for specifics has been trending for some time now, from the clothes to the devices, and it says a lot about our time now. Look at how many have been revived – Nintendo Switch, Tamagotchi, flip phones…I’ve been wanting to get a Gameboy and CD player for over a decade. I prefer the old-school devices in a way. There’s beauty and simplicity in them.’ It feels quite sacred to have separate devices for work and play. Mainly as we have an app for everything and we’re given content that (questionably) shows us what we want to see. It’s maddening when you consider the gluttonous access we have to information and how we in turn, feed algorithms too. It’s no wonder we want a break from the expectation of being online.

Professionally, the smartphone era is a double-edged sword. You can split marketers into three camps – those who’d happily go off grid, the chronically online, and those inbetween. From an arts marketing point of view, anyone can make content from their phone which means that organisations and venues are dealing with critics in the papers, physical visitors, and online communities. We track visitors’ behaviour – how long they watch videos, what brought them to the platform – and design content to fit handheld devices. I’ve barely scratched the surface here on how smartphones have changed the way I work, and I haven’t even touched on the geopolitical and environmental impact of smartphones.

So while there are finer tech wizards who will herald this collapsing distinctions between smartphones as a sign of a ‘matured industry’ gearing towards wearable AI, I don’t think this is the right conclusion to draw. A cost of living crisis has meant mindful consumption and phrases such as ‘echo chambers’, ‘doom scroll’, ‘burn out’, and ‘screen fatigue’ are embedded in our vocabulary. We can’t escape smartphones but we can find a better balance.

So I guess it wouldn’t hurt to start by following Jaz’s suggestion: ‘Maybe it’s worth returning to tradition. Let’s get out the sharpies, the scoobies, and bedazzle our smartphones! Bring back the Gaudy Days!’